Adventure isn’t about looking on a map and planning a trip. It’s about the unexpected magical things that occur while you are out there exploring new territories and new vistas.

And if you’re a scientist, then you’re on a daily adventure looking for answers, new information, new directions, and most of all, discoveries––especially those that can change worlds, both the whole world and your own part of it.

Since my wife and I are some of those individuals who fit both of these words well, becoming a part of Adventure Scientists was a no-brainer.

All we have to do is collect the leaf samples.

So. That sounds easy: look at the maps (cool maps by the way), check the range of the trees in our zone, check habitat characteristics such as water, slope, elevation, and where the land fits the legal/permission criteria and is fairly accessible, and then roll out.

Whoa, there.

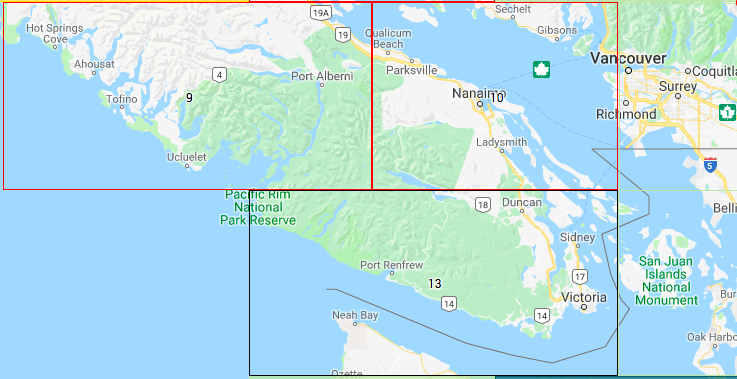

Where we live on Vancouver Island, in the project’s Zone 13, over half of the land is private. And by private we mean owned by logging companies whose interest is in cutting pine, cedar, spruce, and Douglas fir for lumber and pulp––which means that for them, maples aren’t anything they’re concerned with, they’re just in the way.

Much of the remaining land that is available to leaf collecting is government-owned, and is designated Crown Provincial. And that tends to be land that was previously leased to logging companies, logged one or two times, and then re-planted and returned to the government for leasing/harvest in the future. But that usually means that it has been logged of everything and only replanted with conifers.

With only one major highway on the Island, virtually all backcountry travel is on logging roads that are owned and maintained by the logging interests. That means there are only roads to and from harvestable stands, not to or from bigleaf maple habitat.

So now the adventure begins. Our sample trees should be easy to find: just look for Crown Provincial lands on the map, check elevation, water, and slope, master the saw-toss tool we need to use for sample collection, and drive and hike right in.

Whoa, again.

Vancouver Island is part of the last remaining temperate rainforest in the world. Think jungle––think impenetrable underbrush––think vines and brambles and hear that high-pitched whine of, yes, mosquitoes.

On one trip, we follow the map and find that the logging road on the map hasn’t been used in probably 30 years, and is almost completely overgrown. On another we find perfect trees, but we’re looking directly at their tops. The bases are 30—50 feet below us down a steep riverbank. One mapped road makes a beautiful circle to what appears to be three perfect sampling zones––until we come to a washed-out bridge and a 40-mile detour.

And of course the real kicker came on our longest road trip.

We found no accessible bigleaf maples for about 30 miles of back- and front-country roads, so we started heading home. All of a sudden we saw beautiful stands of perfect maples just calling our names. We stopped, took the sample envelope picture and then checked the map. We had crossed into a different collection zone directly north of ours––and samples from there had already been gathered. Argghhh.

But along the way we saw a female mountain lion and her two yearling cubs, a juvenile black bear, several groups of seals, and one very inquisitive sea otter.

But perhaps best of all, we finally found the most perfect old, healthy bigleaf maple––on the grounds of one of our favorite roadside stops, Ice Cream Mountain.

A summer volunteering with Adventure Scientists truly lives up to both sides of the name.