By Kristian Beadle of Green Coconut Run Expedition

Crew member Michael watches the lightning show in Oaxaca, thanks to Hurricane Blanca spinning offshore, photo by Kristian Beadle.

Crew member Michael watches the lightning show in Oaxaca, thanks to Hurricane Blanca spinning offshore, photo by Kristian Beadle.

In the pitch black of a lightening storm off the coast of El Salvador, we steered under instruments alone. Suddenly a bright light shone from the port side of our sailboat. “Look out, it’s a panga!” cried Sabrina through the din of 30-knot winds shaking the rigging. In the disorienting chaos, with sails flapping wildly, our sailboat stalled into the wind, and I swung the wheel to starboard to avoid a collision with the small El Salvadorian fishing boat.

It was four months into the

Green Coconut Run, a cooperative sailing voyage on the 42-foot trimaran Aldebaran. Most people who own large cruising sailboats – capable of sailing across the ocean – are wealthy retirees. We circumvented this financial barrier by creating a sailing cooperative with over 50 participants, each joining for a week or longer. In order to crowd-source the voyage, everyone chipped in money or labor, depending on how much time they were coming aboard.

Near the Ranger Station at the Murcielago Islands, Costa Rica, photo by Kristian Beadle.

As part of our mission to Cruise with a Cause, we joined Adventure Scientists on their

Microplastics Initiative, which seeks to understand the scale and spread of microplastics in ocean and freshwater sources. The project itself is an amazing example of crowd-sourcing: outdoor enthusiasts like us can collect scientific samples, which vastly reduces the overhead costs for researchers and allows them to get otherwise unattainable data.

Sabrina sampling for micro-plastics at the “Magic Log,” a mid-ocean floating log in Mexico, photo by Kristian Beadle.

Sabrina sampling for micro-plastics at the “Magic Log,” a mid-ocean floating log in Mexico, photo by Kristian Beadle.

By definition,

microplastic (less than 5mm in size) is invisible to the human eye. We can’t see them, yet they are in the water column, finding their way into filter feeders, our drinking water, and our bodies.

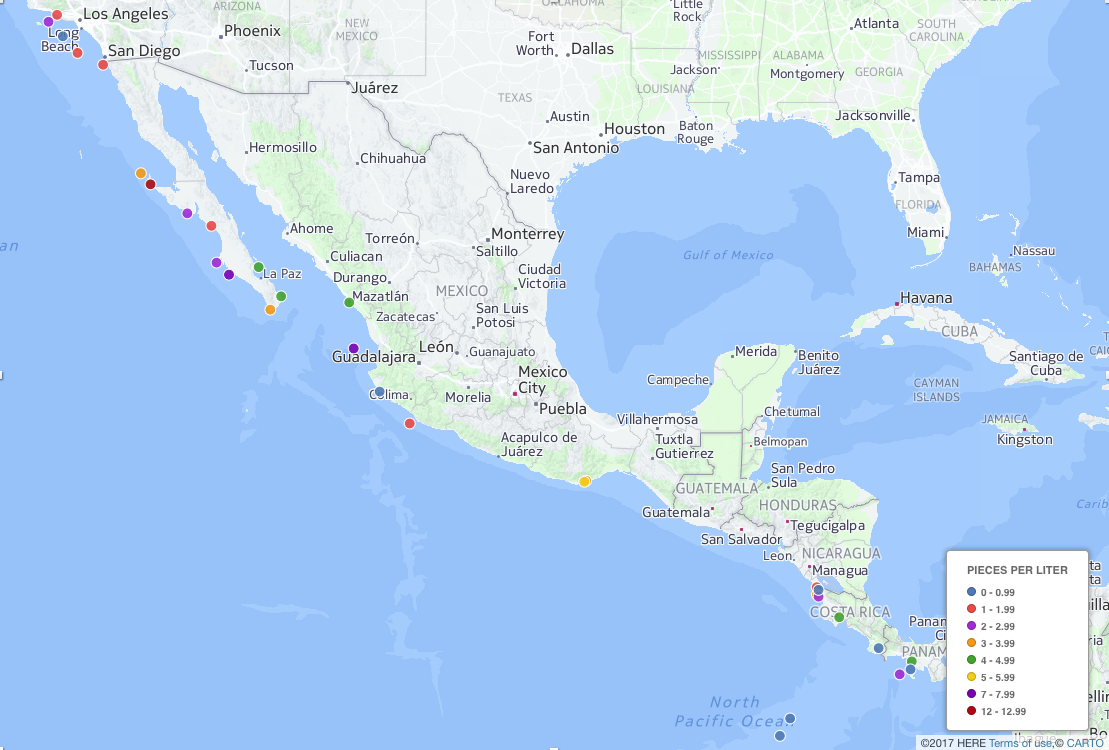

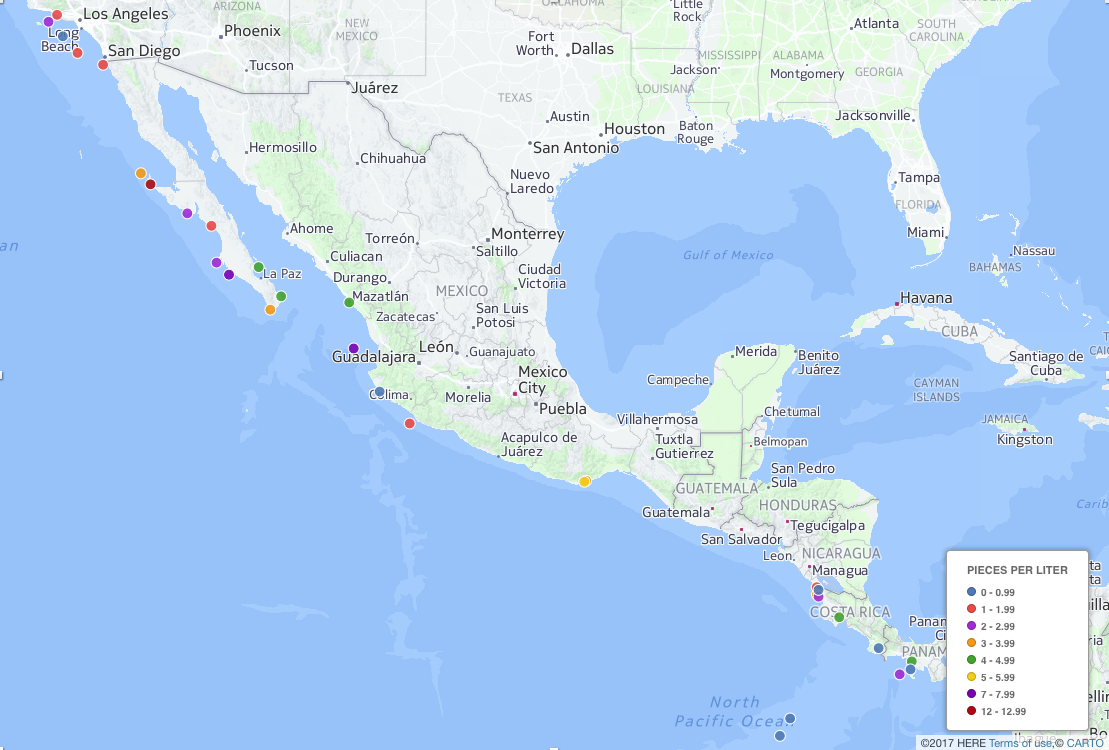

In every country we visited, from Mexico’s Baja peninsula to Ecuador, we took a variety of water samples to show the extent of microplastics in the sea surface. These results reinforced the surprising nature of microplastics: they may occur where you don’t expect them.

The water in Costa Rica’s Santa Rosa National Park looked absolutely pristine. This region was one of the most beautiful marine protected areas we’d seen. Yet our samples averaged 2-3 pieces of microscopic plastic per liter of water.

In the southern Nicoya Peninsula of Costa Rica, currents sweep trash onto Isla San Lucas’ western beaches, photo by Kristian Beadle.

Later we visited Isla San Lucas in the Nicoya Gulf of Costa Rica, which had depressing amounts of plastic debris on its beaches. Piles of fishing nets, water bottles, and even sandals were washed up on the high tide line. We expected those samples to be loaded with plastic, but surprisingly they only contained about 4 pieces per liter.

In contrast, samples from remote places off Baja Peninsula (Natividad, Punta Tosca, Cleofas), had 7-12 pieces per liter, the highest values to date of our 32 processed samples.

After over a year of sailing, we arrived at the ecosystem meccas of Isla del Coco and Galapagos. The islands didn’t cease to amaze from the first moment to last. They take us back to another eon, where animal life was prolific on Earth. We’re happy to report that microplastic samples were virtually nil in these amazing destinations.

In Chamela Bay, Mexico, with Sabrina’s family visiting, photo by Ryan Smith.

In Chamela Bay, Mexico, with Sabrina’s family visiting, photo by Ryan Smith.

Aldebaran has traversed 7000 miles and visited more than 60 islands in the last two years. We are blessed to slowly watch the degrees of latitude move by.

However, it’s disturbing that we found microplastics in 93% of our samples along Central America’s coastline (not counting Isla del Coco and Galapagos). Also, we saw about six islands which served as “magnets” for floating trash, piled high on their beaches, due to the predominant currents.

The sobering sights of our trip bring caution to our excessive use of plastics. Meanwhile, the adventure is uplifting and motivates us to continue bringing awareness to ocean health.

Map of Green Coconut Run’s microplastic sampling locations

Crew member Michael watches the lightning show in Oaxaca, thanks to Hurricane Blanca spinning offshore, photo by Kristian Beadle.

Crew member Michael watches the lightning show in Oaxaca, thanks to Hurricane Blanca spinning offshore, photo by Kristian Beadle.  Sabrina sampling for micro-plastics at the “Magic Log,” a mid-ocean floating log in Mexico, photo by Kristian Beadle.

Sabrina sampling for micro-plastics at the “Magic Log,” a mid-ocean floating log in Mexico, photo by Kristian Beadle.  In Chamela Bay, Mexico, with Sabrina’s family visiting, photo by Ryan Smith.

In Chamela Bay, Mexico, with Sabrina’s family visiting, photo by Ryan Smith.