By: Lauren de Remer

Imagine a trail so steep and rocky that every step is a slide or ankle sprain. Mosquitos relentlessly bite one’s feet. Then add weight: a backpack containing a camera, two liters of water, a headlamp, and enough sunscreen and bug spray to last another week in Zambia’s Batoka Gorge. Its white sandy beaches are tucked between basalt boulders that heat up like an oven by 8 am. The temperature is 104 degrees. The one water sample I neglected to collect during a 4-day whitewater rafting trip is waiting for me at the end of a three hour hike to the mighty and notorious Zambezi River. And so, down I go.

I had taken water samples for Adventure Scientists’

Global Microplastics Initiative before, but this was a much harder task – from finding a one-liter water bottle in Livingstone without a leaky top, to trekking back down to the river to fill it, to ensuring it wouldn’t burst at altitude on my return flight. Adventure Scientists needed more freshwater samples to add to their Global Microplastics Initiative dataset, so I knew I had to find a way to get it home.After all, I’m not here for vacation. I’ve spent 10 years working in adventure travel, and rivers hold a special place in my heart. When I found out that the Zambezi River was (and still is) under threat from a major hydropower project, I found a way to document the story and share it with the world. Six months later, I fundraised enough money to make my trip to the Zambezi River a reality. I wrangled a couple friends to join me and we set out to produce a short documentary about our experience.

It took two weeks to get anyone to open up about the proposed dam on camera. We knew we didn’t have the answers, but we sure had a lot of questions. “Who are we to tell Zambia and Zimbabwe what to do with their river?”I thought to myself. Shockingly enough, I never met anyone who spoke about the ecological significance of it, even with Victoria Falls just up river – a UNESCO World Heritage Site. For many of the locals we encountered, the Zambezi wasn’t a river, it was an asset, an investment that the rest of the world found to be special. I was learning that, in Africa, political, economic, and social issues take precedence over environmental concerns.

|

Some people consider it impracticable to prioritize tourism and river conservation while locals struggle with poverty. I started to think about the endangered taita falcon population that would be impacted by the dam and the energy deficit. Zambia’s external debt and dependence on copper mining all intimately contribute to mounting pressure on social and environmental issues. I wondered if coming here was a waste of time, if our film project and even this water sample, would make a positive impact, or any impact at all.

|

Stumbling down the last section of “trail,” I rehydrated, took in a breath of hot, dusty, African air and hustled over to the rapid slated to be the future dam site. I wiped the sweat off my forehead, found an eddy to bathe and replenish my energy in what some refer to as the river of life. I marveled at the towering sandstone walls above me and let my thoughts fade away. Where I was swimming would soon be underwater – I was in the precise location the Batoka Dam is scheduled to be built. I soaked in the intensity of something larger than myself, grateful for the perspective and seclusion. I’m not religious, but it was certainly a spiritual moment. Three mentors came to mind: Doug Tompkins, George Wendt, Martin Litton, and everything they directly and indirectly taught me about wildness and its sacred beauty. The sun was setting and golden specks of sand shimmered off the water’s surface while swallows dodged the rapid’s spray, feeding on recently hatched Mopani flies. I slipped back into my sandals, let my skin air dry and found a spot below the churning hydraulics to take my sample.

|

As I bent down to rinse my bottle, I looked up and spotted a traditional fisherman across the river just downstream from me on the rocky Zimbabwean bank. There was a fishing camp on river left, but this ambitious man had likely hiked hours – possibly days – to get to where he was and was quite perplexed by what I was doing there. I smiled at him with a wave and calm body language. He watched me sample, I watched him cast his net. We shared a simple moment as the sun fell behind the ridge, he in Zimbabwe, I in Zambia. Two strangers appreciating the river for what it was in its current state: wild, thriving, and (hopefully) plastic free.

|

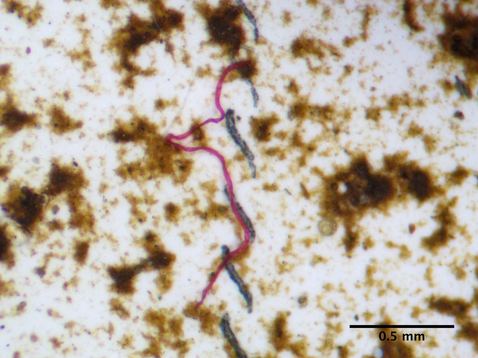

Upon returning back to the U.S., the analysis from the one sample we took at dam site was that it contained three microfibers: one black, one blue and one red. Regretfully, we did not sample for metals to measure the impact of nearby copper mining waste, but Zambia and Zimbabwe are currently facing extreme internal debt while looking to hydropower to meet the region’s energy demands. Zambezi River Authority is still reviewing engineering feasibility studies, environmental & social impact assessment and securing finances for implementation.

Backstay Media is currently in the editing phase to create a short documentary sponsored by O.A.R.S. & Water by Nature entitled, “Batoka” scheduled to release later this year. Please follow our Facebook page to be informed of our progress and future screenings. They hope to launch an online campaign with International Rivers (IR) to coincide with the touring of this film that explores solar as a potential long term energy solution. In the meantime, you may check out IR’s Zambezi River campaign for more information about Batoka Gorge Dam, to donate to the cause or share it with friends.

All photos courtesy of Lauren de Remer

Find out more about our Global Microplastics Initiative and other Adventure Scientists projects by subscribing to our e-newsletter, visiting our website and by following us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.