Alex Suber is a student at Colorado College and the State of the Rockies Videographer. Colorado College’s State of the Rockies Project was founded over a decade ago with the mission to research, report, and engage on environmental issues in the Rocky Mountain West. his summer Alex joined the expedition team on their journey from Colorado to British Columbia and also participated in ASC projects en route.

The view from Glacier National Park. Photo by Alex Suber.

From Alex:

This summer, my expedition team and I headed up north to experience some of the most clear effects of climate change – receding glaciers. We were headed to Glacier National Park, a place that in twenty years might not have a single glacier left. Glaciers that took tens of thousands of years to form are disappearing in mere decades there. These glaciers visually convey climate change in such powerful ways that I felt compelled to capture them all.

While preparing to journey to glacier country, I remembered a presentation by Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation (ASC) at the State of the Rockies conference last spring. ASC offers the opportunity many explorers dream about – a purpose. I quickly went online to learn more about the projects they offered. It was just weeks before our team was set to head into the wilderness when I logged onto the website and, within minutes, found exactly what I was looking for: the repeat glacial photography initiative through Alpine of the Americas Project (AAP).

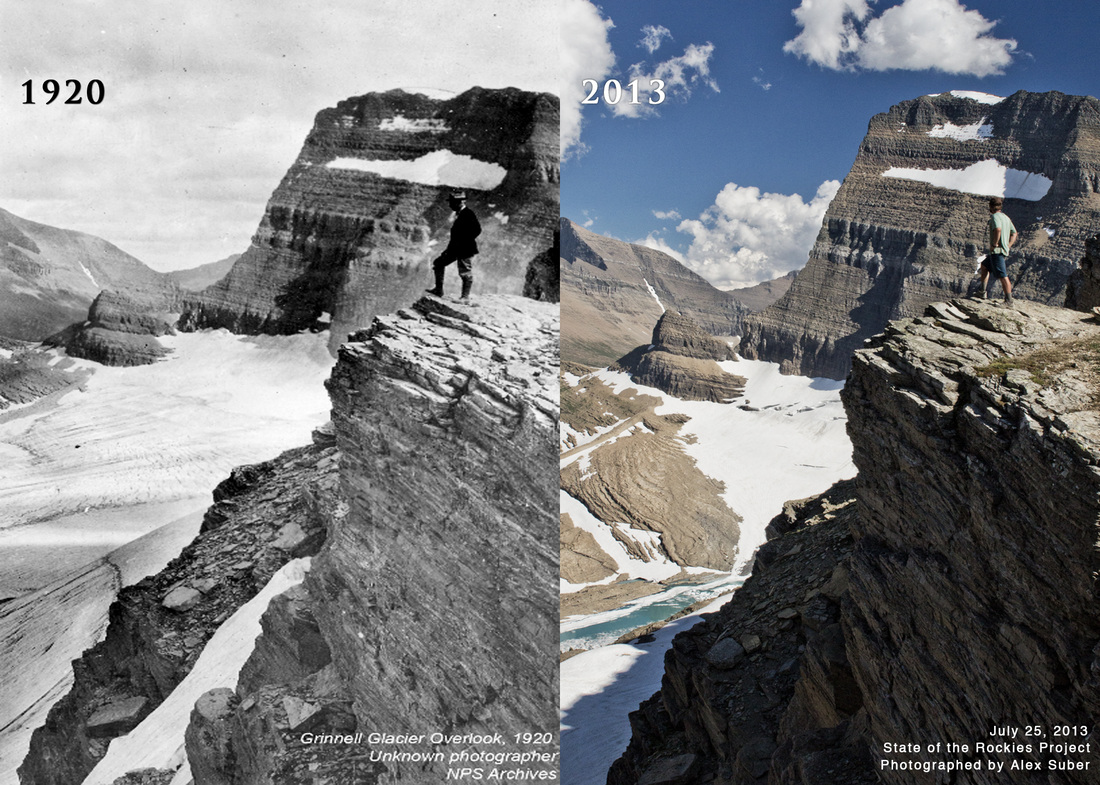

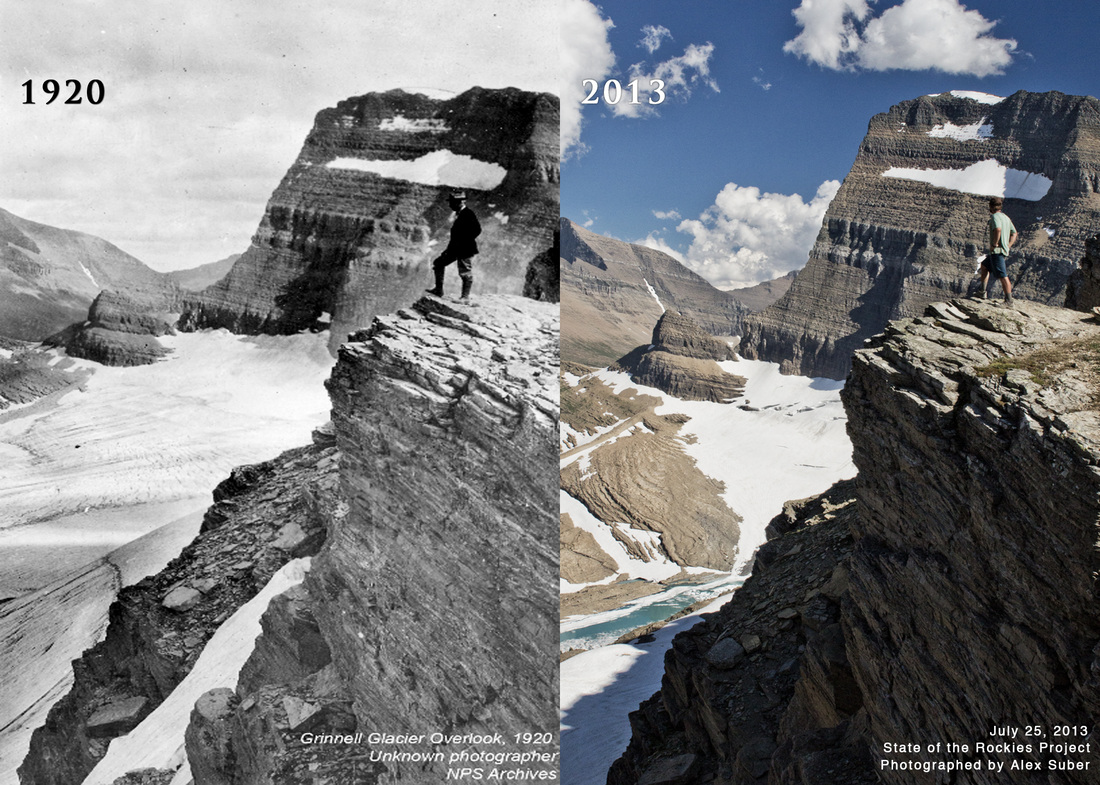

Grinnell Glacier, then and now. Photo by Alex Suber.

AAP aims to provide climate scientists with useful observations of alpine change. They have been collecting repeat-glacier photography from around North America for a number of years and now partner with ASC to recruit volunteers. It was the perfect match for our trip and, within a few hours, I was connected with a researcher from the project.

In addition to the glacial photography project, we also participated in ASC’s wildlife observations project. We promptly set up an account with iNaturalist, an online citizen science platform, and geared up to document wildlife along the way.

With historical photos and cameras in hand, we set out to hike and raft throughout the Rockies, eventually finding ourselves face to face with the relic of Grinnel Glacier in Glacier National Park.

Paddling glacier country. Photo by David Spiegel.

“You know, one day I’m going to show this picture to my kid and there will be no glaciers left,” one of my fellow researchers lamented as he snapped a picture of himself in front of Grinnel. In that moment, I knew we were onto something powerful: we were documenting history in the making as glaciers retreated around us. This wasn’t abstract science that we were doing, this was real and tangible. As five young adults in our twenties, the experience became personal. Gazing at Grinnel Glacier and looking back at the photo, taken in 1920, that I held in my hand was frightening. Of the 150 glaciers in Glacier National Park in 1850, only 25 remain. Even more alarming is that scientists predict by 2030, none will remain.

Mountain Goat (Oreamnos americanus) are among the species that may be affected by retreating glaciers. Photo by David Spiegel.

As I turned behind me and looked at the lush valley fed by Grinnel glacier, I recognized we were seeing climate change first-hand and I began to understand the monumental implications. Not only would these majestic sights be gone, robbing Glacier National Park of its namesake, but life in the valley below would also change, losing its glacial water supply. It was a stark realization. The pine forests, summer wildflowers, and mega-fauna that define the Rocky Mountains are living on borrowed time. All of our time photographing and identifying wildlife suddenly took on new meaning and, with it, a more defined purpose.

“As the water moves, so will the animals.” And people. Photo by David Spiegel.

I realized that the photographs and observations of elk, deer, coyote, foxes, and wildflowers we had recorded for

ASC’s project were incredibly useful. We were part of an online community that was identifying individual species. And with GPS based locations, these sightings revealed an extensive network of wildlife populations and their distributions. In the light of climate change and the disappearance of glaciers, it is going to take a mass effort to track these species. As the water moves, so will the animals.

Friendly fox. Photo by David Spiegel.

The two contrasting photos of Grinnel Glacier made climate change real to me. The dots started to connect and the interdependence of these vast ecological systems was obvious. And something else became clear: if we can collect data and understand how melting glaciers like Grinnel are affecting wildlife migrations and distributions, then we, as the adventure community, can make a differencre. By enlisting athletes and adventurers to collect data, we can expand our understanding of how climate change affects wildlife and the wild places we love. With the help of adventurers acting in conjunction with research scientists, the possible scope of scientific data collection broadens tremendously. This is the dream and purpose of ASC. With knowledge, comes to power to create solutions. This is exactly what we need in order to begin to tackle the threat of climate change.

Camping under the starry sky. Photo by David Spiegel.

The mood, as we stood above Grinnel Glacier, was somber and the feeling intense. As young adventurers, I think that watching glaciers disappear before our eyes brought a lot of things into perspective. We have all known that we live in a rapidly changing world, but we weren’t prepared to witness the environment around us evolving so quickly. Now that I’ve lived my dream. I’ve stood where another long-forgotten adventurer stood almost a century ago and documented the same – but at the same time very different – glacier. I have gained new direction and another dream has been born. I’m determined do something about it, and being a citizen scientist felt like a step in the right direction. Platforms like ASC are blurring the lines between scientist and explorer, naturalist and adventurer, and that is a necessity as we addresses the large-scale issues that face our planet.

You can get involved with the glacier repeat photography project or the wildlife observation project by filling out afind an advisor form. Explore our map to see other projects near you. Keep up with others like Alex by subscribing to ASC’s blog, liking us on Facebook and following us on Twitter (@AdventurScience).