Banded Gulls along the Atlantic Coast: Boating & Beach-walking for Science

Why Study Gulls?

Gull populations along the east coast of Canada and the U.S. have undergone dramatic fluctuations during the past centuries. In the 1800s, they were hunted extensively for their eggs and feathers and many populations were decimated. Gulls (and other seabirds) were legally protected from hunting in the early 1900s. As a consequence of legal protection and increased availability of garbage and fisheries discards, many gull populations grew exponentially. During the past decade, however, some gull populations appear to be declining, possibly because many landfills have either closed or are being more actively managed to reduce gull numbers.

Gulls are often found in places where people live because we provide them with many useful resources including food and housing (did you know that some gulls nest quite happily on roof tops in cities?). Gulls are often considered nuisance species because they are so common in urban and suburban areas where some of their interactions with people are viewed negatively. However, gulls are also integral members of natural biological communities. As top predators in coastal marine food webs, gulls can dramatically alter the composition of marine invertebrate communities. At islands where they nest, gulls contribute critical nutrients, derived from their marine prey, to soils and terrestrial plants. They are also important competitors and predators of other species of seabirds.

Surprisingly, for many populations of gulls, little is known about their distribution, habitat use, and population dynamics. There are several studies taking place in Atlantic Canada and the U.S. that are geared toward gaining a greater understanding of gull biology. In some cases, studies of gull biology are being done so that managers can make more informed decisions about how to reduce the negative effects of gulls on other species of conservation concern. There is also growing interest in understanding why some populations of gulls, which used to be very abundant, are now decreasing significantly. When common species start to decline, scientists become concerned about potentially serious environmental issues.

How can Citizen Scientists Help?

The presence of uniquely marked individuals in a population provides researchers with invaluable data on movement patterns, survival, habitat use, reproductive success, and many other aspects of gull biology. Researchers are often only looking for marked gulls at their study sites. Observations from citizen scientists who are searching for marked birds over a large geographic area enable scientists to learn far more than they would on their own.

How will this data be used?

Researchers need observations and photographs of banded gulls to help them to determine where gulls go in the winter, how far juveniles disperse during their first few years of life, the survival rate of adults and juveniles of both species, and behaviors (e.g. foraging, scavenging, aggressive interactions) of gulls when they are not in their breeding colonies where originally banded. Volunteers can record the location of banded birds, their band numbers, behavior, and take a digital photo to document each re-sighting. Resights of banded gulls will contribute substantially to our knowledge of these common, but underappreciated birds. Resights and photos may also be posted at the Gulls of Appledore blog.

Gull populations along the east coast of Canada and the U.S. have undergone dramatic fluctuations during the past centuries. In the 1800s, they were hunted extensively for their eggs and feathers and many populations were decimated. Gulls (and other seabirds) were legally protected from hunting in the early 1900s. As a consequence of legal protection and increased availability of garbage and fisheries discards, many gull populations grew exponentially. During the past decade, however, some gull populations appear to be declining, possibly because many landfills have either closed or are being more actively managed to reduce gull numbers.

Gulls are often found in places where people live because we provide them with many useful resources including food and housing (did you know that some gulls nest quite happily on roof tops in cities?). Gulls are often considered nuisance species because they are so common in urban and suburban areas where some of their interactions with people are viewed negatively. However, gulls are also integral members of natural biological communities. As top predators in coastal marine food webs, gulls can dramatically alter the composition of marine invertebrate communities. At islands where they nest, gulls contribute critical nutrients, derived from their marine prey, to soils and terrestrial plants. They are also important competitors and predators of other species of seabirds.

Surprisingly, for many populations of gulls, little is known about their distribution, habitat use, and population dynamics. There are several studies taking place in Atlantic Canada and the U.S. that are geared toward gaining a greater understanding of gull biology. In some cases, studies of gull biology are being done so that managers can make more informed decisions about how to reduce the negative effects of gulls on other species of conservation concern. There is also growing interest in understanding why some populations of gulls, which used to be very abundant, are now decreasing significantly. When common species start to decline, scientists become concerned about potentially serious environmental issues.

How can Citizen Scientists Help?

The presence of uniquely marked individuals in a population provides researchers with invaluable data on movement patterns, survival, habitat use, reproductive success, and many other aspects of gull biology. Researchers are often only looking for marked gulls at their study sites. Observations from citizen scientists who are searching for marked birds over a large geographic area enable scientists to learn far more than they would on their own.

How will this data be used?

Researchers need observations and photographs of banded gulls to help them to determine where gulls go in the winter, how far juveniles disperse during their first few years of life, the survival rate of adults and juveniles of both species, and behaviors (e.g. foraging, scavenging, aggressive interactions) of gulls when they are not in their breeding colonies where originally banded. Volunteers can record the location of banded birds, their band numbers, behavior, and take a digital photo to document each re-sighting. Resights of banded gulls will contribute substantially to our knowledge of these common, but underappreciated birds. Resights and photos may also be posted at the Gulls of Appledore blog.

To participate in this study, please tell us about your expedition.

Protocol for Reporting Banded and Wing-tagged Gulls: click here.

Datasheet for collection of field data: click here.

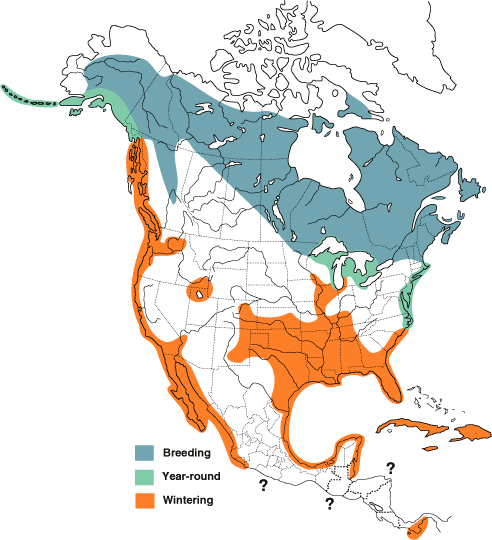

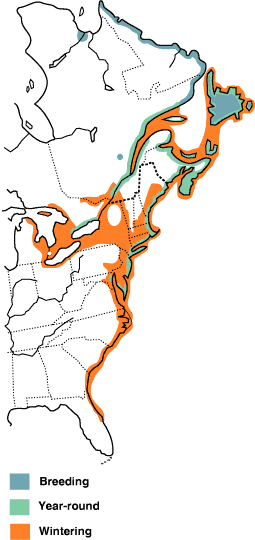

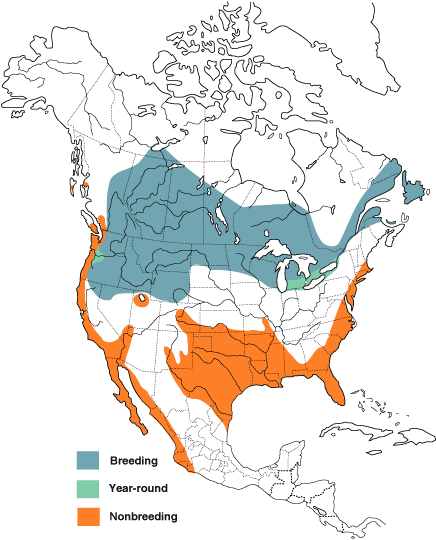

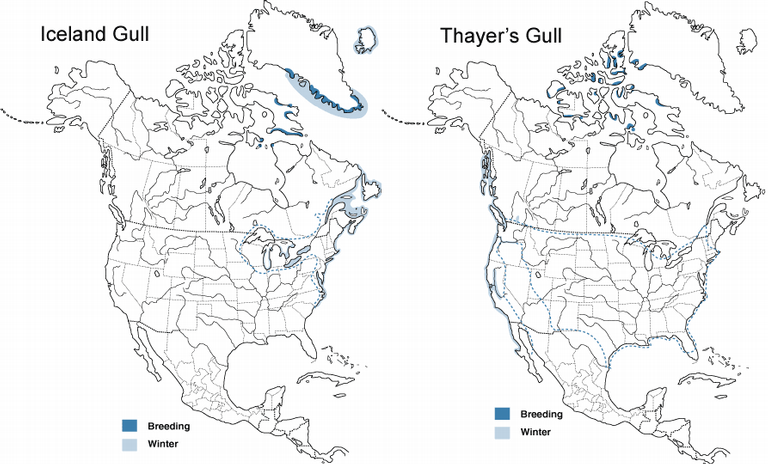

Range Maps: